Media Room

Articles / News

Scarfone Hawkins LLP Announces Alexander Smith as Newest Partner

Scarfone Hawkins LLP is proud to announce that Alexander Smith has been admitted to the partnership, effective January 1, 2026. His practice includes banking and

Celebrating 50 Years of Evolution: A Night to Remember

An evening to celebrate our law firm’s evolution over 50 years servicing the Hamilton Region.

Sultans of Swing: Wrapping Up a Baseball Season of Team Spirit and Fun

This year, our firm’s softball team, the Sultans of Swing, reminded us just how much fun a work life balance can be.

Honouring Truth and Reconciliation Through Action

Brantford Native Housing has broken ground on a landmark affordable housing project, creating 18 supportive units for Indigenous families, seniors, and individuals.

Lawyers Featured in The Best Lawyers in Canada™

Six Scarfone Hawkins LLP lawyers have been recognized in The 2025 Best Lawyers in Canada™ edition for excellence across multiple practice areas.

Two Outstanding Lawyers. One Big Announcement

Celebrating New Leadership: Matthew Cino & Jordan Moss Join Our Partnership

Local Champion Sponsor for the Hamilton Edition Run for Women

Proud Sponsor of the 2025 Shoppers Drug Mart Run for Women Hamilton

Proud Bronze Sponsor of La Dolce Vita Night for Ladies Who Give

We’re delighted to be a Bronze Sponsor for the La Dolce Vita night, hosted by the Ladies Who Give organization.

Congratulations to Jennifer Vrancic on Her Appointment to the HLA Board of Trustees

We are proud to share that Jennifer Vrancic, one of our esteemed associates at Scarfone Hawkins LLP, has been appointed to the Board of Trustees

Adam Savaglio Named Finalist for Canadian Lawyer’s Top 25 Most Influential Lawyers

Adam has named a finalist for Canadian Lawyer’s Top 25 Most Influential Lawyers in the Human Rights, Advocacy, and Criminal category.

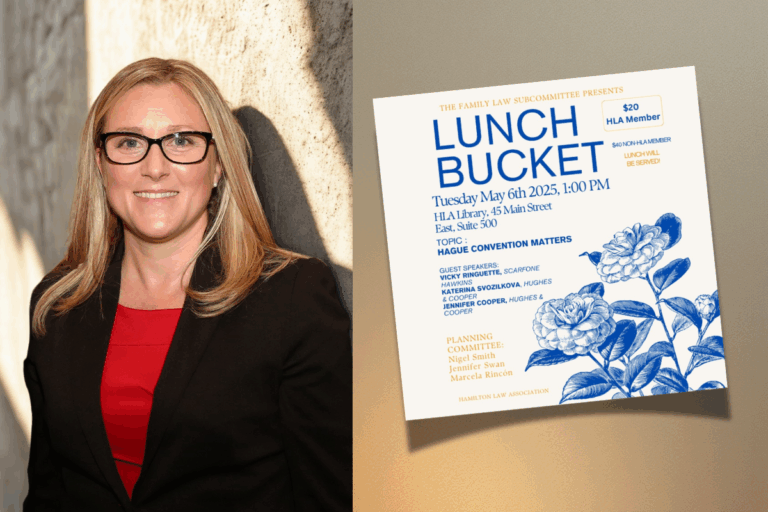

Join Vicky Ringuette at the Hamilton Law Association Lunch Bucket Event

We’re excited to announce that Vicky Ringuette, Partner and leader of our Family Law practice, will be a featured speaker at the Hamilton Law Association’s

Racing Towards Robotic Surgery Innovation: Scarfone Hawkins LLP ATB2025 Team

Scarfone Hawkins LLP joined the 2025 Around the Bay Road Race once again in support of St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton. This year’s fundraiser focused on

Scarfone Hawkins LLP Wins Outstanding Business Achievement Award at Hamilton Chamber Gala

2025 Large Business Category in the The Hamilton Chamber of Commerce has announced the winners of its annual Outstanding Business Achievement Awards (OBAAs) night: Scarfone

Honouring the women who shape our future

Young lawyers should seize every opportunity to have actual “facetime” before a Judge and to feel the tingle of excitement and nervousness that comes with

Wish I may, wish I might

Written by Kayla A. Carr. We look at whether the expression of a “wish” in a Will was simply a wish that created an unenforceable

Fifty Years in Law: Honouring Our Past and Building Our Future

This year marks a milestone for Scarfone Hawkins LLP. 50 years of serving our clients with integrity, innovation, and dedication. We’re looking ahead to the

Managing Partner Danielle Iampietro Finalist for National Women of Influence Award

Scarfone Hawkins LLP proudly celebrates Managing Partner Danielle Iampietro as a finalist for the prestigious RBC Canadian Women Entrepreneur Awards, presented by Women of Influence.

We’ve Been Named One of Canada’s Best Places to Work

Scarfone Hawkins LLP is proud to be named one of Canadian HR Reporter’s Best Places to Work in 2024. This recognition reflects our commitment to

Celebrating Alexandria Palazzo – Hamilton’s 40 Under Forty

We’re proud to celebrate Alexandria Palazzo, recognized as one of Hamilton’s 40 Under Forty Business Leaders for her outstanding contributions to family law and our

The Virtues Of In-Person Hearings

Young lawyers should seize every opportunity to have actual “facetime” before a Judge and to feel the tingle of excitement and nervousness that comes with

Companies are implementing vaccine mandates. Can employees reject them?

Scarfone Hawkins LLP’s Employment Law expert Adam Savaglio discusses with the CBC, the misconceptions and incorrect assumptions about the law around vaccination mandate.

The Sirloin Cellar and James Street Alleyway

David Thompson recollects his memory of the James Street alleyway, a narrow covered paved road surface running east off James Street North directly south of

Memory Book Update

David Thompson takes us back to 1973 and outlines a summation of the history and development of Scarfone Hawkins LLP until today.

Our Day at the Supreme Court of Canada

David Thompson and Matthew G. Moloci recount a visit to the Supreme Court of Canada in a proposed class proceeding against 407 ETR.

Practical tips for the courtroom seminar

There are two components to advocacy: written advocacy; and the oral presentation.

Supreme Court Of Canada Calls For “Culture Shift” In Civil Justice System

On January 23, 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada released its long-awaited decision in Hryniak v. Mauldin, 2014 SCC 7, a decision on Ontario’s Rule

Silver Lining for Creditor Spouses in Bankruptcy?

When dealing with personal bankruptcies/proposals, family law issues often rise to the surface, which are not easily or sufficiently resolved within the parameters of federal

Considerations in Administering Class Action Settlements

A presentation co-authored by David Thompson & Mary M. Thomson outlining considerations in administering class action settlements.

A Judicial Shift in the Enforceability of Termination Clauses

One of the emerging issues in Ontario law has been the judicial rulings against termination clauses in an employer’s offer letter or employment agreement, which

Advising Clients on the Purchase of a Condominium

As a result of the introduction of the Condominium Act, 1998, R.S.O. 2001, as amended; (the “Act”), a number of new condominium development options were

The Sale of a Business: One Giant ‘Beauty Contest’

While business law is not often correlated to spectacles filled with baton twirling or snippets of autobiographical monologues, there are times when a business will

Escrow Closings

It is surprising the number of lawyers who do not appear to fully understand the full extent of their obligations with respect to escrow closings

Land Titles Act Applications

This paper addresses the means by which a property owner may make application to convert the title of the property from either Registry to Land